Hooks presents a new way of looking for me, a new way of viewing cinema. She describes a look as being “confrontational, as gestures of resistance, challenges to authority (Hooks,247).” When viewing with an oppositional gaze, it’s obvious that mainstream cinema continues to be very problematic due to its unequal representation of minority groups, as well as its overrepresentation of wealthy white people.A cult classic, Mean Girls(2004) is a great example of this.

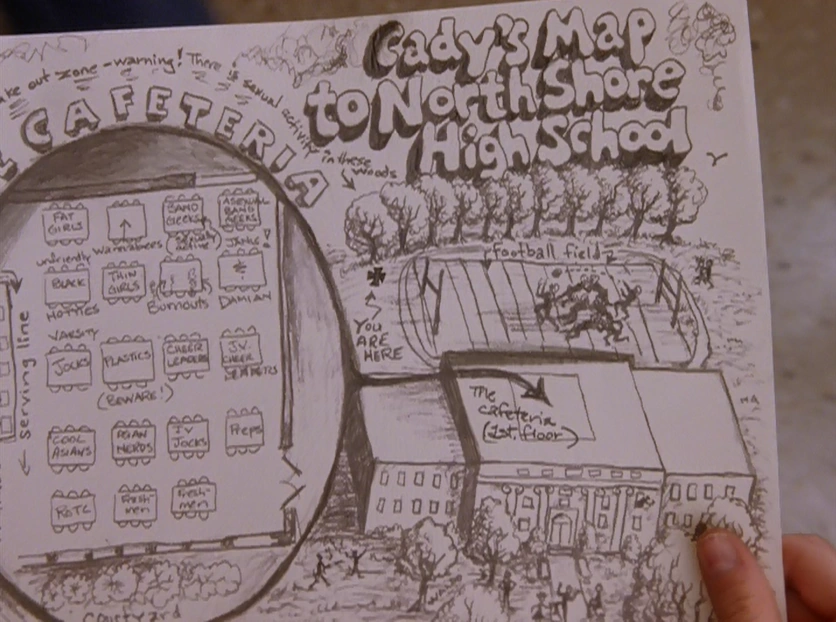

The dominant representation of this movie is a lighthearted comedy of a girl just trying to find her place in the hierarchy that is high school after being homeschooled her whole life. The protagonist, Cady has just moved from Africa to Illinois to attend public high school for the first time. She finds herself with the popular clique, the “plastics”, who are all white, wealthy and stereotypically pretty. Everyoneat school wants to be like or with Regina George, the leader of the Plastics. The problem with this dominant representation is that it portrays the white woman as more desirable than other races. This film also focuses a lot on race and separates groups based on their race and general personality. For example, the cafeteria is divided into groups like “cool Asians”, “nerdy Asians”, “unfriendly black hotties”, etc. They most often associate being popular with being wealthy and white.

This all becomes apparent when you view the film with an oppositional gaze with lens of race, gender and class. As previously discussed, all of the main characters that are viewed as appealing happen to be white.“…black female spectators have had to develop looking relations within a cinematic context that constructs our presence as absence, that denies the “body” of the black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is “white” (Hooks, 250).” This is true for Mean Girls, with no people of color playing a significant role, and when there is a person of color they’re being stereotyped. Along with this, the females are shown are extremely sexualized. Regina and her clique are constantly obsessing about their image and weight, and in addition to this they put others down for not conforming to their definition of pretty.

Mulvey’s theory of male gaze is another dominant theme. She comes to the conclusion that “The woman displayed has functioned on two levels: as erotic object for the characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium (Mulvey, 33).” The plastics are constantly dressed to impress, with rules dedicated to not wearing sweatpants and wearing pink on Wednesdays. Apart from this, they are constantly being looked at by men and women, for pleasure and always under scrutiny. This act of being looked at is evident during the Halloween party and the talent show especially. They describe Halloween as being the one time of the year that you can dress like a “total slut” and no one judges. All the girls dress in lingerie and animal ears in an attempt to look sexy and appeal to the men at the party, at one point we can see two females kissing and two men cheering them on while they watch. This is an obvious example of Mulvey’s male gaze, using the women as an object for the male sexual pleasure. They also serve as an erotic object for the audience watching the film. During the talent show, the Plastics are dressed in sexy Santa outfits and dance in a way that can be observed as provocative. In this scene, a male character approaches a different girl and says, “damn, rather see you out there shaking your thang” outright objectifying and reducing her value as a person, a very common theme.

When viewing with a lens of economic class this film continues to show how problematic it really is. The fact that the plastics as all wealthy is made apparent to the audience from the very beginning and is meant to add to their appeal. It is pointed out that Gretchen’s father invented the toaster strudel and is extremely wealthy. We also quickly find out that Regina lives in a mansion and is not modest about it. Even Cady, although her house is more modest, lives very comfortable with two successful, educated parents. This is a concern when analyzing the movie because similar to the lack of women of color, the lack of lower class portrays the superiority of the wealthy. This wealth also aligns closely with the hierarchy of the high school, the more money you have the more popular you are despite your personality.

One might argue that this is just a comedy and harmless satire. However, this film is still relevant to this day and has had an influence on the youth. All films are very purposeful and thought out. “The filmmaker and the editor watch the collected footage over and over, deciding which portions of which takes they will assemble into the final cut of a movie. They do so with the same scrutiny that was applied to the actual filming. Even if something occurred on film without their planning for it, they make a conscious choice whether to include that chance occurrence. What was chance in the filming becomes choice in editing (Smith, 128).” Every detail of mean girls was scrutinized by multiple people who were all very aware of the messages that it was sending to its audience. All aspects from using the “R” word multiple time to the lack of colored cast members, along with all the other problematic factors the film portrays.

References:

Hooks, bell. (2002). “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation.

Mulvey, Laura. (1975). “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16(3), 30.

Smith, Greg. (2001). “’It’s Just a Movie”: A Teaching Essay for Introductory Media Classes.” Cinema Journal 41(1), 127-134.